My neighborhood—most of my city, actually—is currently undergoing a dramatic change, the likes of which I have not seen in my two decades of residency. I first began to notice that something different was occurring in the autumn of last year, but in recent weeks the transformation has become undeniable and unavoidable. Its duration and its effects on the local population remain to be seen.

Simply put, my street is swimming in a new deluge of propaganda. Over the last half year over two hundred large propaganda posters have been hung on the gates and walls of the tiny alley where I live—the vast majority of them in the last few weeks. The posters are large, colorful, and rarely repeat, demonstrating the high degree of financial commitment behind this effort. Nor is this new propaganda initiative limited to wall posters: in the past week I have seen slogans appearing on bus stop walls, on “bus TV” (the video screens displaying local news and information on the city buses), in full-page newspaper advertisements (if the government owns the papers and produces the “ads” are they ads or editorials?), on the back of cash registers in the local supermarkets, and—most surprisingly—sent as SMS to the video displays in the dashboard of our local taxis. One friend even found a smaller version of one of the posters stuffed under his front door early one morning. Called “public service advertisements (公益广告),” the different posters are sponsored by a variety of local entities from block associations to municipal-level “civilized city” offices.

For those of us raised in the West, propaganda is a frightening term, carrying with it visions of Orwellian message control and manipulation of facts. The Chinese term xuanchuan (宣传), however, is a much more neutral or even positive term. In the Chinese context “propaganda” is primarily information that the state conveys to the public, and since this information comes from such a reliable source propaganda is generally considered (in the mainland Chinese sense) to be trustworthy.

The Core Values of Socialism . . . Prosperous Strength, Democracy, Civilization, Harmony

The content of the vast majority of the propaganda announcements in my neighborhood comes from the official list of the “Core Values of Socialism” (社会主义核心价值观), a long list of pat “values” that taken together are supposed to capture the unique and essential aspects of Chinese socialism. Including things like equality, freedom, democracy, and peace—as well as filial piety, patriotism, dedication to one’s profession, and “prosperous strength”—these twelve concepts are all part of what is supposed to make up “the China dream.” Most of the propaganda posters along my street highlight one of these virtues, along with various texts and images designed to explain the virtue and encourage “appropriate” behaviors.

Democracy is the good prayer of human society.

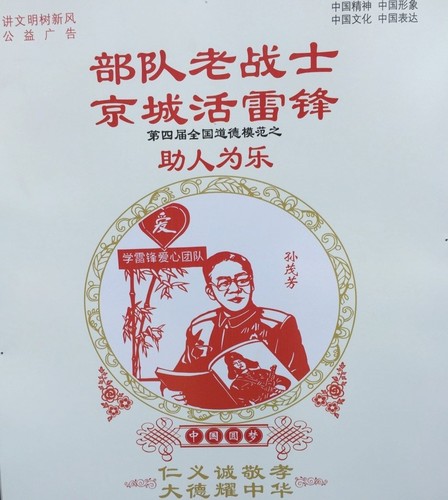

In addition, there are a handful of other themes that find their own sets of posters. One set features a series of national heroes who are “exemplars of the virtues of Chinese socialism.” Significantly, these biographical posters all emphasize the “the joy of helping others” (助人为乐) a kind of Chinese version of the Golden Rule.

Sun Maofang, “Beijing’s Living Lei Feng”

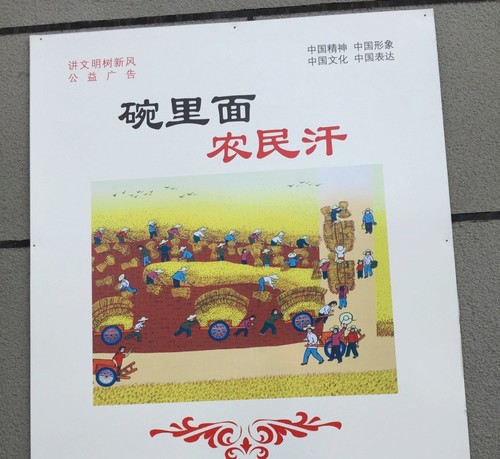

Another series of posters emphasizes the importance of grain to China, and the importance of hard work and frugality in preserving the nation’s grain supply. These—even the style of the artwork—seem like a throwback to themes from decades in the past.

The noodles in your bowl are the sweat of the peasants.

Yet another series emphasizes the importance of protecting China’s youth, stressing the importance of healthy homes, good education, and the relationship between today’s youth and the nation’s future.

It is the shared responsibility of all of society to allow children to grow up happy and healthy.

Many posters, of course, encourage citizens to raise their “quality” or suzhi (素质). This word, used so often and with so little irony, can include anything from education level to the cultural habits that mark membership in China’s upper classes. Most Westerners view the term as a derogatory slander used to dismiss China’s rural population from participation in society, and yet its usage persists throughout all sectors of official and unofficial China. This particular example, below, also demonstrates another new aspect of this campaign: did you notice how many children are in this family?

Strengthen ethical mastery; increase civilized quality.

The list goes on: the importance of natural resources and the cost involved in procuring and preserving them, the essential social role of filial piety, the need to protect the environment, and instructions for all sorts of “civilized behavior” (including the proper ways to ride buses, ride bicycles, drive cars, and cross streets) all have their place in this propaganda campaign. No message, however, is more simple yet more poignant than that old standby of subservience to the state: Lei Feng. The example I included below is particularly striking, as it clearly links Lei Feng to traditional China—and not the revolutionary years—locating both Lei Feng and traditional culture with the red chop mark in the bottom right: Zhongguo meng, “the China Dream.”

Study Lei Feng, our good exemplar.

Why all this? And why now? Local people (who have all noticed the change) claim they are paying little attention to this new wave of information. One local acquaintance suggested this was the sort of image control the state likes to engage in before the nation takes stock of its past and future prospects during Chinese New Year. But the volume and insistence of this current media putsch is orders of magnitude beyond what has been typical. And when the content of these messages is viewed within the context of new regulations restricting foreign participation in Chinese society, the anti-western thought campaigns within the education and cultural production sectors of society, and China’s more assertive approach to foreign relations, the fog clears and this campaign can be seen clearly for what it is: yet another indication of the Chinese Communist Party’s determination under Xi Jinping’s leadership to roll back the clock on all forms of potential ideological liberalization throughout Chinese society.

It is easy for those of us raised in societies with a tradition of free press to dismiss government propaganda as ham-fisted and easily ignored. But in societies where other voices are marginalized if not suppressed, the state’s ability to influence public thought should not be underestimated. I asked one older friend, a retired government employee, if he thought most people noticed the messages or paid attention to their content—implying that I imagined most were pretty numb to this kind of persuasion. He surprised me with his answer: most civilized or better educated people, in his estimation, would not only read the notices, but actively try and study their meanings. Perhaps his response should have been expected, particularly in light of the return of weekly political study sessions (and quizzes!) in government agencies and state-owned enterprises over the last two years.

As I said at the beginning, the duration of this campaign and its ultimate effect will not be known for some time. And the lack of anything really “new” in these slogans raises many questions about China’s vision for the future. Closer to home, the scale of this campaign signals in a clear way that the state is quite serious about managing not just the activities that expatriates carry out in China, as the new January 1 Overseas NGO regulations address, but more specifically the ideas that lie behind many of those activities. This new stage of “social control” (社会管理) is nothing less than an attempt by the state to win the hearts of the Chinese people—and to shape those hearts in ways that conform to the Party’s notion of the China Dream. The precise content of the China Dream is no longer up for debate. Still not sure what it means? Just read the posters in your neighborhood.

Image credit: All images courtesy of the author.

Swells in the Middle Kingdom

"Swells in the Middle Kingdom" began his life in China as a student back in 1990 and still, to this day, is fascinated by the challenges and blessings of living and working in China.View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.