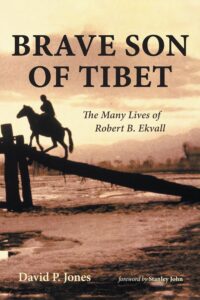

Brave Son of Tibet: The Many Lives of Robert B. Ekvall by David P. Jones. Eugene, OR: Resource Publications-Wipf and Stock, 2023, 274 pages. ISBN-10: 1666769037; ISBN-13: 978-1666769036. Available from Wipf and Stock and Amazon.

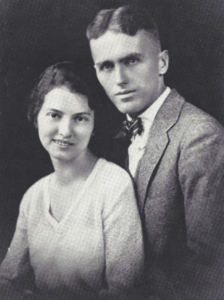

Brave Son of Tibet tells the interesting story of Robert Ekvall. In a mix of Robert Ekvall’s challenges and eagerness to explore and push the limits, Robert’s life had many turns and bring us a very engaging story. Robert was born in China, on the border of the Tibetan areas. His parents were sent with the Christian and Missionary Alliance (CMA). Robert got his feeling for language and deep understanding of culture when he grew up bilingual and was exposed to the different cultures and lives at the border between Chinese and Tibetan life. Life was tough and death was frequent along the path. His Swedish father had already died by the time he was 14 years old. He followed in his parents’ footsteps and after some years of study and working as a writer he returned as a missionary to China with his wife Betty.

The mission assigned them to work in China as he had superior knowledge of Chinese language and culture. The leadership strategically appointed them to work for the mission school. Robert showed his character and strong thinking in pursuing his and Betty’s vision to explore the Tibetan field and pushing further into these areas than any earlier CMA missionaries. CMA leadership acknowledged Robert’s deep knowledge of Chinese language and culture and wanted him stationed in the Chinese area to support the church and mission school. Robert accepted his mission but worked on a second agenda to pursue his heart for Tibetan areas by extensive journeys to explore and study Tibet. Throughout his life we can see his adventurous spirit to push further and cross common borders. At this time, we are also exposed somewhat to the tension about spiritual gifts and baptism between the CMA and Pentecostal movement. But Robert and Betty still joined with the Halldorfs, Swedish Pentecostal missionaries, on their exploration to the unknown Tibetan areas.

It intrigued me as a reader how Robert as a reader of culture also pushed in how to share the gospel and tell the gospel. We can see in a special dialogue when the Tibetan man named Legs started his journey in belief.

He [Legs] spoke—carefully, precisely—as though stating an equation of mathematics. “If Buddha is right and Christ is wrong, even if I follow Christ I only lose my religious chance in this life. There will be another rebirth and I will have another chance. But if Buddha is wrong and Christ is right and I do not accept Christ, then I am lost to the endlessness of time. I will believe” (p. 100).

Journeys in Tibet and Sharing the Gospel

Robert had also a unique knowledge in how he used and understood relationships to accommodate travels into hostile areas, where they needed to prepare host-guest relationships in any new area to make these journeys of exploration and sharing the gospel. It has baffled me how hostile Tibetans can be, or in a kinder way, not welcoming to new people, and people have told me that it is because of being very isolated. However, I know other isolated areas, and they are even more hospitable than less isolated areas. Robert worked around this by always asking for an introduction and becoming a guest of a host in the new area. As he prepared each visit in this way it was certain that he and his companions would be received and able to stay in a new town or village. Even when they were not really welcomed, because of this relationship they still received a place to put up their tents and at least got some time for an audience. It was also a way to be protected on the roads when robbers attacked, because they could claim a relationship to the host, and the robbers had to give up or else they would face the host’s power.

It was also a good reminder that in this furthest northeastern part of the Tibetan areas, they gave out the sections of the gospel that were translated into Tibetan and produced by the Moravian church in Ladakh, the most southwestern part of Greater Tibet. As it was given as a gift it was always received, and Robert always wrapped it in a Khada (a traditional ceremonial scarf) to show respect to the gift and to the receiver.

Robert and Betty went to the untamed Tibet and built relationships, preparing for themselves and others to move and live in these new areas. Robert was a visionary with deep understanding of the cultures, but also brave, as the title says, facing local robbers, politics, and later, war-haunted China. It certainly is a different style as missionary to ride with a rifle in hand, and most of the time it was enough for two or three of them to carry weapons to scare away the robbers, whose weapons were of poorer quality. This knowledge and experience were collected in the many books, articles, and unfinished material Robert wrote. It was writings on request and his own longings, plus many reports. He had a very good analytical and strategic mind, which we can see in his approach to mission but also affirmed when he served in the military later.

Unfortunately, it seems it was a bit of a sore spot to never get fully recognized with a title or in the eyes of some academics. Robert had studied at Bible school as a young man, but for most of his life he was a practitioner and received his understanding and skills from those around him who had experience and knew the way of life. He was an author and writer all of his life, and as such very good even in his youth, when he worked for a secular company writing. However, he did not have formal degrees or credentials to gain acceptance from professors and academics. Nevertheless, Robert was still very much at home in his field, as we can see from his many titles and analysis, both for mission and as a military strategist.

Robert was born in 1898 and lost his mom in the 1930s. Eight years later, his wife Betty passed away while their son David was at boarding school in what is now Vietnam. Robert struggled with trying to find his way back as a missionary in Tibet, but the war times forced him to leave, and he stayed with David until he had been repatriated. It took a few years for David to give up waiting to go back to Tibet and be repatriated in one of the exchanges between the US and Japan. During this time Robert had started to gather military intelligence and smuggled it, risking his life for the American authorities. After this Robert was not able to return to the mission field, except for some trips with the mission when he was very old. He decided to join the military to gather intelligence and establish relationships during World War II and later in the tension between communists with Mao and the Republic of China. At the end of the World War II, David enlisted and went to South Korea, where he died in a bomb accident, leaving Robert all alone.

Military Career, Second Wife, and Further Travels

This starts the second part of Robert’s life and of the book. We follow Robert after this drastic turn but with the same character of deep understanding and bravery. He surprised many superiors with his unique language skills, but also how he knew and related to many people of power. His unique skill in drawing out information from people was observed by Ce Roser, a Chinese American and wife to the US consul, and she expressed to Bob, as she called Robert: “Bob, it is not fair. It is not fair what you do to the Chinese. You question and talk with them until they forget that you are a foreigner, and you get them to turn themselves inside out to tell you everything—even what they shouldn’t tell. For the first time in my life I begin to feel defensive on behalf of the Chinese when they begin to talk with an American. It’s not fair” (p. 176). The many horse and yak journeys had now turned to jeep rides and flights, but still exploring and travelling uncharted roads. It even brought him to Urumqi, Xinjiang in the middle of the war and local warlords. While traveling, Robert was able to reunite with old friends, Tibetan and Chinese, as well as some of the important church and mission officials. However, life was very different from earlier, where now it was high society in diplomatic and governmental relationships. It was in a sense a move from having a Bible in hand to now a glass of wine.

This second part of life had also brought a new wife, less than half his age who had a strong character as Betty had had, and against all common expectations she travelled with him in all these hostile regions from Burma to Kazakhstan. Eva never shared his faith, and we can’t really see Robert’s faith surfacing again until old age. Robert and Eva continued to live in the front, and in between the powers until it came to a halt in 1950 when the communists had won. At that time Eva gave birth to a son, named Eric and later a daughter, called Karin, and Robert became a father again in his 50s. Robert continued to write, and wore his soldier’s uniform off and on for different requests from the military. His last position was as a translator in the North–South Korean conflict. He was ever diligent in his Chinese, sense of culture, and good strategic understanding. He lost his second wife to cancer before their children became teenagers.

It is a book well worth reading, not the least as Robert Ekvall’s life is very interesting and never boring. But within the stories you have to consider the life of Tibetans, how the gospel is shared and how relationships are birthed and grown. It is a challenge to follow a man like Robert who lived on the edge and watched with open eyes in the most demanding and dangerous situations. I wish I could have got a lot more of insight into Robert’s view on both his faith, missiology, and contextualization. It is a good reminder to read of the Chinese leader Mr. Chu for the Chinese church, who was replaced by the far away leadership. Mr. Chu had led the church for 30 years, and Robert was uncomfortable to take over and supervise a much older and more experienced man. Robert wanted to focus on Tibet and made it clear that Mr. Chu would pastor the church and be in charge, while Robert would stay to support and help. Robert received the appointments from home but managed it his own way. “Robert knew that this kind of thinking’s days were numbered. The release of leadership to nationals in the growing Chinese church needed to be done, and the ‘three-self’ indigenous principles implemented” (p.22). Robert had a strong opinion that appointing leadership from headquarters far away was paternalistic.

I truly enjoyed this biography and was intrigued to read more and study more deeply what Robert wrote, not just the scattered reading I have done. I’m thankful for a first book describing Robert Ekvall’s life from beginning to the end, so I will give some grace to the minor inconsistences seen, being the author or the source, in some of the described context. Mission stories and travel journals can easily list stages and events, but this is not that kind of book, instead it leaves the reader to contemplate the life of a man with a sharp mind facing sorrows and dangers on a life journey on the edge of impossibilities.

Our thanks to Wipf and Stock for providing a copy of Brave Son of Tibet: The Many Lives of Robert B. Ekvall by David P. Jones for this review.

Image credit: Raimond Klavins via UnSplash.

Chris Gabriel

Chris Gabriel (pseudonym) is a dedicated networker and strategist deeply committed to serving God's people, especially those in the least reached regions. Over the past 25 years, he and his wife have tirelessly worked in Asia, empowering communities in various creative access areas. Today, their six grandchildren are doing their …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.