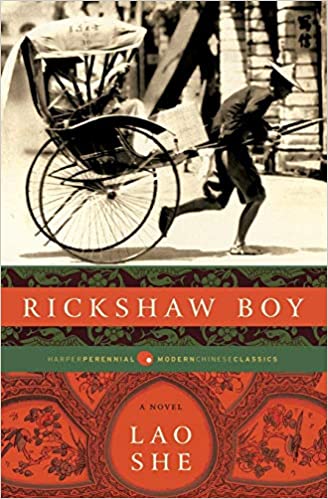

Rickshaw Boy by Lao She, translated by Howard Goldblatt. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Chinese Classics. Translation copyright 2010 by HarperColins Publishers. 322 pages. ISBN-10: 0061436925, ISBN-13: 978-0061436925. Available from Amazon and most likely your public library.

He did not smoke, he did not drink, and he did not gamble. With no bad habits and no family burdens, there was nothing to keep him from his goal as long as he persevered. He made a vow to himself: in a year and a half, he—Xiangzi—would own his own rickshaw. (Lao She’s Rickshaw Boy, p. 9)

Individualism: Belief in the primary importance of the individual and in the virtues of self-reliance and personal independence.1

Can poverty rob a man of his soul? Can betrayal by the things you love most break the constraints of the God-given conscience and society’s mores? Rickshaw Boy challenges the reader with these wrenching considerations. Though set in a bygone era in a culture that has since been transformed by globalization, Lao She speaks to us clearly—perhaps even more so than to his contemporaries.

Though the protagonist Xiangzi’s ethic of individualism is a ruling passion for most in the developed nations of today’s world, it was very rare in his China. Likewise, Xiangzi’s striving for “personal peace and happiness in his own private space” is currently a goal for millions. However, Lao She rings alarm bells that we should each heed.

Xiangzi, the rickshaw boy, was born in the countryside of China. After the deaths of his parents and the loss of their property, he moved to Beiping, as Beijing was then called. Being big and strong and good-looking, Xiangzi decided to sell himself to the public as a rickshaw boy and earn his own support in this fashion.

Having no money to buy a rickshaw, Xiangzi had to join a stable of rickshaw boys and pay a portion of his take to the owner of the vehicles. He always believed that his combination of strength, patience, and willingness to work diligently would soon provide him with the funds to purchase his own rickshaw and financial independence. This is just what transpired.

It was a wonderful rickshaw that within six months seemed to develop a consciousness of its own. When he twisted his body or stepped down hard or straightened his back, it responded immediately, giving him the help he needed. There was no misunderstanding, no awkwardness between them . . . When he reached a destination, he’d wring puddles of sweat out of his shirt and pants . . . Exhausted? Sure. But happy and proud. (p. 15)

However, Xiangzi had been born poor and, according to author Lao She’s social ethic, Xiangzi was destined to die poor. The rickshaw man was at last reduced to earning his subsistence as a hired mourner at funerals.

Respectable, ambitious, idealistic, self-serving, individualistic, robust, and mighty Xiangzi took part in untold numbers of burial processions but could not predict when he would bury himself, when he would lay this degenerate, selfish, hapless product of a sick society, this miserable ghost of individualism, to rest. (p. 300)

In many ways Lao She, like his protagonist Xiangzi, was in the wrong place at the wrong time. His biography speaks of his baptism as a young adult in 1922 in the Gangwa City Church. He then suffers when identified as a Christian by the Red Guards, though his wife comments, “After marriage he never attended church or said grace before eating . . . he only admired Christ and made friends with others, and he carried the spirit of salvation, not bound by any forms.”2 The same article in the China Christian Daily that quotes his wife goes on to say, “The character that most possesses Jesus’ spirit is Xiangzi in “The Camel Man.”3 In it Lao She gives the Camel Man, Xiangzi, the characteristics of Jesus—tenacity, responsibility, courage, love and sacrifice.”

The last look at Xiangzi, the Rickshaw Boy, depicts a hopeless, worthless, empty man whose compelling goal is to find discarded cigarette butts with a few puffs left. The last look at Lao She in his biography depicts a hopeless, empty man who apparently drowns himself in a nearby lake after returning home to find Red Guards ransacking his home and destroying his manuscripts. (p. Xii, Introduction) Neither Xiangzi or Lao She had a faith sufficient to see them through the difficulties of life.Rickshaw Boy offers a compelling and sobering look at pre-revolutionary China.

Lao She’s depiction of the streets of old Beijing and life inside the walls of her compounds is depressingly realistic. It delivers fresh insight into the “why” behind the Chinese leap from the frying pan of a feudalistic society into the cauldron of communist totalitarianism. Little did the world foresee that the individual would have even less value in a Marxist society than under an imperial one. Then the Cultural Revolution exploded, and it knew.

Endnotes

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 5th edition.

- Li Daonan, Christian Faith and Literary Works of Famous Chinese Novelist Lao She, China Christian Daily 10/19/21. Trans. Charlie Li http://www.chinachristiandaily.com/news/china/2019-06-28/christian-faith-and-literary-works-of-famous-chinese-nolivest-lao-she_8416 (accessed October 28, 2021)

- “Camel Man” is a nickname for Xiangji arising from an incident in the book, Rickshaw Boy and was an alternative name for the book. See Amazon for an example.

BJ Arthur

BJ Arthur (pseudonym) has lived in China for many years and was in Beijing in June 1989.View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.