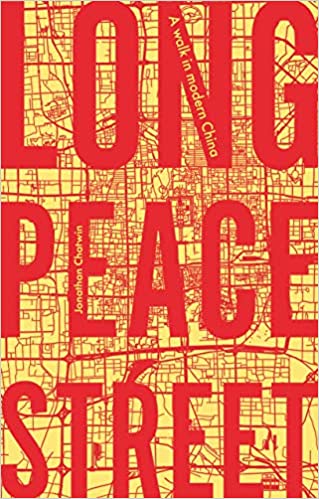

Long Peace Street: A Walk in Modern China by Jonathan Chatwin. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019, 264 pages.

I had the privilege of living in Beijing for almost 15 years. On its face, there’s not that much about the city to like. It’s too big. It’s too loud. It’s too square and boxy (I can think of only one or two roads that don’t run north/south or east/west. The traffic and the air are terrible. It has some of the strangest architecture in the world.

But during the years I lived there I grew to love this city, where history was lurking in every nook and cranny. And when I tired of the history (almost never) I could jump to the gleaming shopping malls and fancy (and not-so fancy) restaurants of the present.

I consider myself a Beijinger. I left eight years ago this month and miss it. A lot. If there was ever a book to grip me with homesickness for Beijing so visceral it almost hurts, Jonathan Chatwin’s Long Peace Street is it.

During the summer of 2016, the author, a resident of Beijing at the time, decided to walk the length of the street known as Chang’an Jie (长安街) that cuts a horizontal swath through the city. Chang means long, or eternal; an means peace; and jie means street. It is most often translated as the Avenue of Eternal Peace, but the author has opted for Long Peace. Beijingers (locals and expats) just call it Chang’an.

Nineteen miles from end to end, Chang’an serves as the horizontal axis of the city, running:

arrow-straight and ten lanes wide in places, through the heart of the city. At its mid-point, Chang’an Jie splices the very centre of the Middle Kingdom, separating the Forbidden City, the expansive residence of generations of Chinese emperors, from Tiananmen Square, the shadowless public space built by the Communists to reinforce the glory of New China. (p. 2)

His plan was simple, namely “to cover the distance from this westerly point to the eastern suburbs over two days—enough time to allow for pauses and diversions—reaching the centre-point of Tiananmen Square by the close of my first afternoon.” (p. 2)

I’m always interested in new and fresh ways of framing history, and I loved this story of Beijing (and China itself) as told through the road. For Chatwin, it is a history that is ordered “not chronologically, but geographically.” He writes:

The street came to seem to me the equivalent of a geographical core sample, in which, just as each layer of the cylindrical rock relates the story of a physical era, so each intersection, each building, each sign and statue seemed to have something to say about the decades of turbulence which begot modern China, and which continue to crucially influence the way the country views itself and its future. (p. 4)

Walking from the far western end of Long Peace Street in Shijingshan to its far eastern end in Sihuidong, unfolds the city’s history, moving from the present to the past to the future; from the industrial to the imperial to the commercial. All along one road.

Some of the destinations that readers who join him on this walk will visit include Babaoshan Cemetery, where the luminaries of Communist China are laid to rest; the Military Museum, Tiananmen Square, and the entrance to the Forbidden City; the Imperial Observatory, and Beijing’s new gleaming Central Business District.

His descriptions and stories revived my own memories of exploring the city by bike with my teammates in the late 90s, early 2000s. We would set out from our residence on the west side of town and head for Tiananmen Square, ten miles away. Along the way, we explored back alleys, and stumbled on obscure historical sites. When needing a break, we could re-enter the modern world and pop in at McDonald’s or Starbucks for sustenance. The co-mingling of ancient and modern was always a source of fascination and surprise. Every single location that he wrote about evoked my own special memories.

In the end what does one say about Beijing? How can it be described? When I lived there, I would tell first time visitors that it was a village with 20 million people. The author struggles with this question as well, concluding that “modern Beijing is a mess, a glorious mess.” Expounding, he writes that the city is:

noisy, endlessly sprawling, confounding to navigate, and echoing with the muffled shouts of those who chafed against its impositions: physical, spiritual, political. Rather than hearing those voices, the city seemed instead to rouse itself now only for the promise of more change; change without considered thought, without anything but a call to action, a picking up of hammers and pickaxes and drills, and bang another new building, bang another new road, bang another lost hutong, bang another accreted layer of concrete and steel ringing around it.” (p. 216)

For anyone with a relationship to Beijing (short or long), this book is a must-read. For those looking for a fresh and accessible framing of Chinese history, this is a great place to start.

For my part, it just made me homesick.

Bang! I miss Beijing!

Image credit: Scott Meltzer, via needpix.com

Joann Pittman

Joann Pittman is Vice President of Partnership and China Engagement and editor of ZGBriefs. Prior to joining ChinaSource, Joann spent 28 years working in China, as an English teacher, language student, program director, and cross-cultural trainer for organizations and businesses engaged in China. She has also taught Chinese at the University …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.