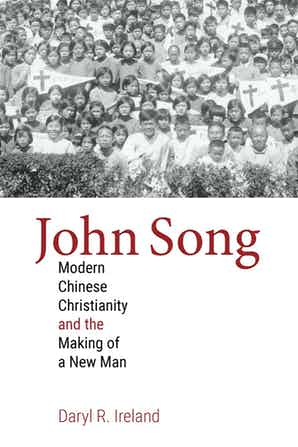

John Song: Modern Chinese Christianity and the Making of a New Man by Daryl R. Ireland. Baylor University Press, 2020, 268 pages. Available from Baylor University Press and Amazon.

The May Fourth Movement fueled an explosion of public conversations about the future of the nation. Debates and radical ideas, many of which had been simmering in university classrooms for decades, now boiled over. . . . Approximately five hundred new magazines appeared between 1919 and 1923. . . . Just as the May Fourth events spread by using baihua, so the new journals printed their articles in the vernacular. The change was akin to what happened when European national languages supplanted Latin as the means for expressing philosophical, literary, and social concerns. (p.6)

The Paris Peace Conference, which convened in January 1919 in Versailles, France, brought relief to much of the world, tired of a war that had resulted in fatalities of some twenty million and casualties of another twenty million plus. However, as the terms of the treaty signed in Versailles became public, the people of China reacted very differently.

Anger and resentment hiked over the mountain ranges, spilled down tributaries, and generally pooled in schools across the land. Even Gutherie Memorial High School in Putian, Fujian Province, got pulled into the vortex of events. The isolated Methodist school, immured by the ocean on one side and encircling mountains on the other, witnessed students organizing political rallies, and the large brick building became the scene of young people shouting and chanting, demanding something better for China. Presumably among them was a short, gangly preacher’s kid—a rather indistinguishable pupil in the mob. [John] Song Shangjie, like tens of thousands of others, watched the power of the May Fourth Movement sway an entire nation (pp. 3–4).

Daryl R. Ireland, in his colorfully descriptive and meticulously documented work, John Song, Modern Chinese Christianity and the Making of a New Man, captures the raging passions of a wronged people who, having sacrificed so many of their own men in World War I, see only more loss and humiliation in the Versailles Treaty settlement. According to the terms of the treaty, all of China’s territory occupied by Germany during the war is not returned to China, but rather given instead to China’s long-time and bitter enemy, Japan. Ireland describes an outcry, eerily similar to the Tiananmen Square demonstrations of 1989 and a likewise harsh government response which followed. The students of 1919, like their modern counterparts, were more than ready to fill the jails, having carried their sleeping bags to the demonstration just in case. More than a thousand were arrested in Beijing alone. However, in 1919, the general public had not yet been cowed into submissiveness. Women marched to the imperial palace to demand the release of those arrested. Strikes in support of the students were widespread— “even beggars, prostitutes, and singsong girls refused to work” (p. 4).

The May Fourth Movement seemed to set off a self-appraisal in a newly awakened society. Even though the Versailles Treaty, hated by the Chinese, was still signed and Qingdao was still ceded to the German government, the students—in Ireland’s words— “had begun something new.” He cites the appearance of “approximately 500 new magazines” in the years between 1919-1923. These journals appeared in “baihua” or conversational Mandarin rather than the literary Chinese that had been the sole medium of literature previously. This was only one manifestation of the great social evolution under way. “The ancient distinctions between those who did mental and physical labor, and between those who ruled and those who were ruled, began to crumble. Elites sought a new type of relationship with China’s workers, industrialists, and farmers. They wanted to create a kind of intimacy and solidarity with the masses that could be leveraged to move them” (p. 6).

In the midst of these monumental changes, John Song had followed a traditional path and traveled to the US for his seminary education intending to become a pastor. When he was forced home in 1927 after his exile from Union Theological Seminary for insanity, he was at first unable to connect with the newly awakened local people in his hometown. He had a passionate desire to evangelize them, but discovered along with other returning elites, that he now had to talk with people about local concerns not preach to them. Song keyed in on local spiritual interests and learned that people were not interested in the latest ideology or doctrine, but in stories “in which the supernatural world penetrated the natural world” (p. 60). He began to share the revelations that he received while he was held in the insane asylum after being committed by the administration of the Seminary.

Back home in Fujian, “Song turned his mental illness into his biggest draw. . . . His story re-enacted a popular trope in Chinese fiction. In book after book, Chinese readers learned to expect that a spiritual genius would reject the normal world because he understands higher things, while the normal world would, alas, reject him because it does not” (p. 62)

As Ireland talks of Song’s activities and experiences, he also gives interesting insights into the social conditions of the several major Chinese cities in which Song spoke. He notes that women were a definite majority and then discusses at length the transformation of China’s women: first she became the “modern woman” in dress, education, and business; then she morphed into China’s civic-minded New Woman on her way to becoming man’s equal—Rosie the Riveter as depicted on Communist posters.

John Song’s faith healings are also documented in Ireland’s work.

Healings were often dramatic. A woman who had been paralyzed for eighteen years stood up after Song prayed for her. ‘She arose immediately and walked from the missionary’s home where the healing took place over to the church, and has been walking ever since,’ assured Southern Baptist Missionary Mary Crawford. (p.193)

Ireland notes that Song was careful to give God all the credit for these healings.

. . . testimonies after the fact [of healing] were required to create a miraculous healing. God had to be narrated into the story of a person’s physical change. Song provided those opportunities by always setting apart time in his services for people to ascend the platform and give a brief word about their spiritual and physical healing.” (p. 193)

John Song: Modern Chinese Christianity and the Making of a New Man concludes with an effective summary of the reasons Christianity has flourished under a repressive Chinese communist government. Ireland lists four features “central to its durability and dynamism.” (p. 204–203) First is the prominent role of charismatic individuals free from government control; this is possible because of the courage of both the leadership and the laity of the Chinese Church. Second is the importance of faith healing in a population without access or resources to obtain good health care outside of the urban areas. Third, and perhaps most important early in the Church’s growth, is the extraordinary use of personal evangelism, especially among women. Feelings of hopelessness in the lives of China’s peasants caused them to quickly identify and seek after the hope they saw present in the spirit of their Christian neighbors. Fourth is the emotional and spiritual strain of rapid urbanization on a populace that for centuries had been 85% agrarian. By 2019, 60% of mainland Chinese were living in urban areas.

There is a fifth feature that Ireland has overlooked in his excellent work: the embracing of Christianity by many influential Chinese intellectuals. Chinese Christianity is no longer the domain solely of China’s peasants who were said to believe because they had no other source of possible joy. It is now the lifeblood of much of her productive middle class and influential intellectuals. However, kudos to John Song as, in Ireland’s words, “the archetype and exemplar of what came to be the most popular Chinese expression of the Christian faith,” (p. 207) and to Daryl Ireland for his excellent work on the life and influence of John Song Shangjie.

Editor’s note: Following the hanyu pinyin, the English name John “Song” is used in the book and in this review rather than John “Sung.”

Image credit: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. John Song is on the left.

BJ Arthur

BJ Arthur (pseudonym) has lived in China for many years and was in Beijing in June 1989.View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.