“Jyrgal” from Kyrgyzstan and I sat on our couch talking about why he was studying in China, the beauty of the Kyrgyz mountains—and the claims of Jesus. I could do this with no Kyrgyz visa, no extra language, and no flight to Bishkek—he came to me.

My friend “Lalit” from Indian Kashmir and I are reading a gospel together. “Tesfay” matured in his faith while in China and returned to a persecuted church in Eritrea. Portuguese-speaking students from Mozambique, Angola, and Brazil meet together to study the Bible. These are some of the almost half a million international students in China, arriving from every corner of the globe.

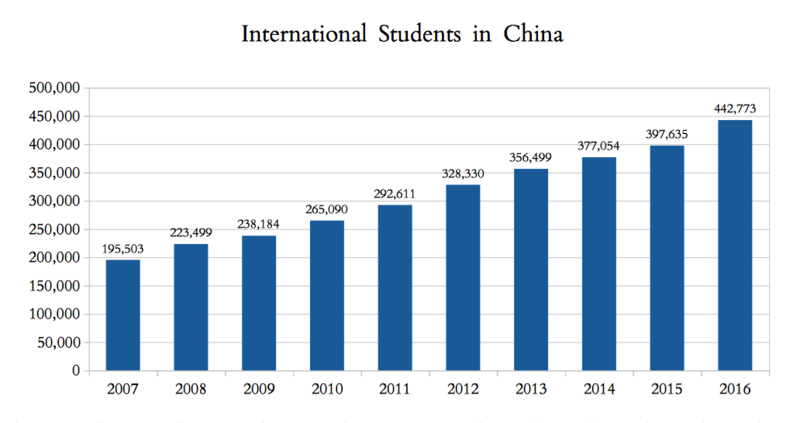

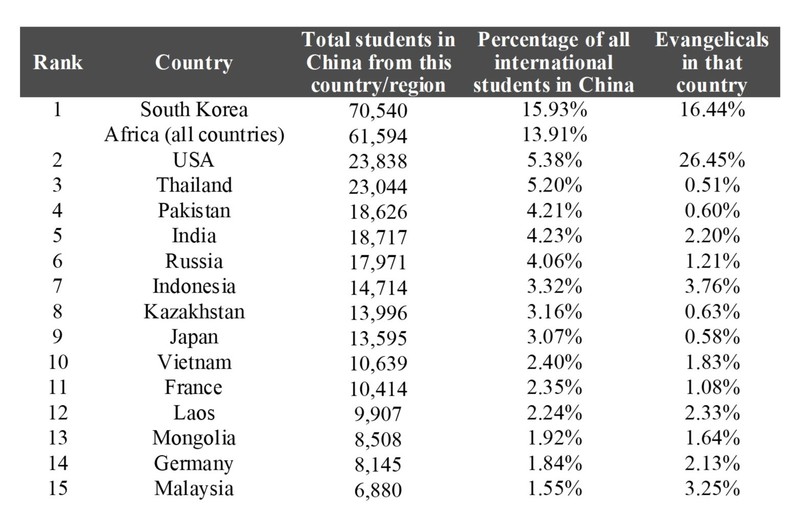

Hardly anyone knows that China is the third largest destination for international students worldwide, after the USA and the UK.[1] With 442,733 international students in China during 2016, this number has grown rapidly over the past ten years, up 11.4% on 2015. Beijing attracted the most students with over 77,000 (17%), followed by Shanghai (14%) and Jiangsu Province (7%).[2] With such high (and growing) numbers and such diversity, is China the “hub of hubs” for impacting the world through international students?

A confluence of powerful factors means that China will continue to strengthen as a destination for international students. China has some of the world’s top universities,[3] is much cheaper than western destinations,[4] and boasts a great diversity of universities and programs. In China 829 colleges and universities accept international students,[5] with many offering undergraduate and postgraduate courses entirely in English. Moreover, Chinese universities are gaining a reputation as attractive research environments.[6] And the country’s outward-facing international education strategy for 2020[7] combined with massive investment by way of scholarships on offer (49,022 in 2016)[8] has attracted many students.

International students account for only 0.9% of total higher education in China, compared to over 20% in the UK and Australia, giving China’s higher education sector huge scope to welcome more foreign students.[9]

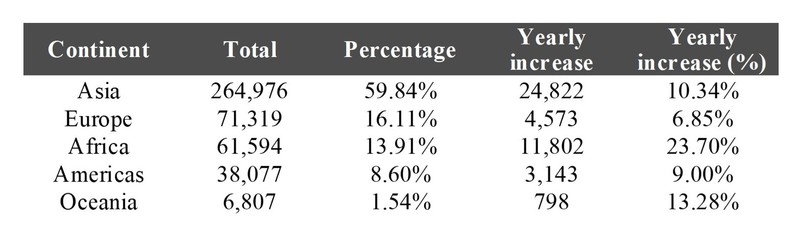

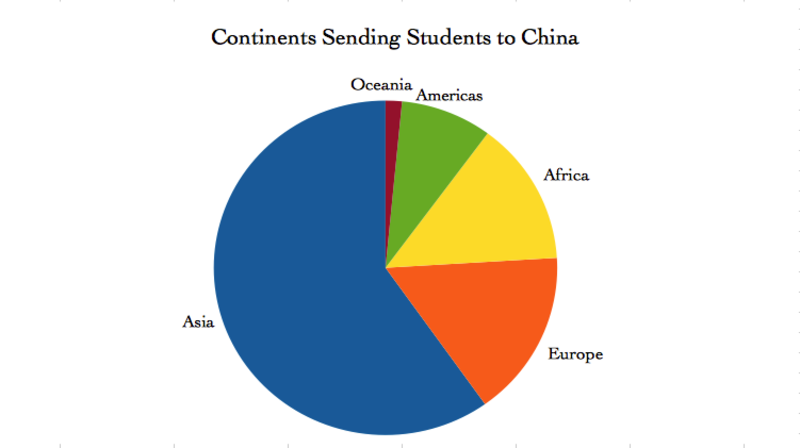

A further explanation for this growth is the rise of “glocal” students—those who pursue a foreign education while remaining in their country or region.[10] Almost 60% of the students come from Asian countries. It is cheaper and culturally more comfortable than going to the west.

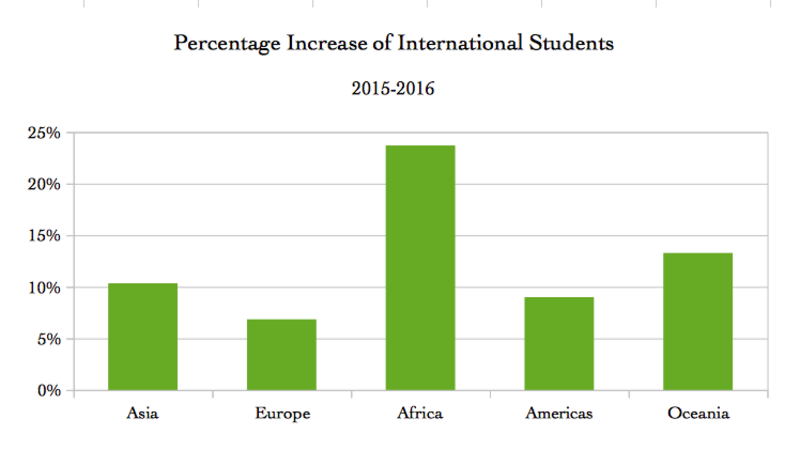

But it’s African students that have increased at a staggering 23.7% year-on-year from 2015. Scholarships from both China and sending countries drive this growth, as does China’s proactive and engaging geopolitical stance especially in strengthening bilateral economic relationships. If African students are considered together they form the second largest group of international students in China, with almost 1 in every 7 being African.

Looking at things from a kingdom perspective, significantly, students coming from most of the top 15 sending countries are unlikely to hear the gospel back home.[11] But in China they can freely visit an international fellowship or hear from believing classmates they interact with daily.

There is a mind-boggling diversity of cultures and languages amongst international students in China. Though radically different from each other, in many ways they can be considered together as a diaspora—a group of people maintaining strong connections with their home culture but living temporarily in another.[12] This however, is a heterogenous diaspora gathered from almost every country and region of the globe. Linguistically, while a lot of international students have some functional English, many have none. So Chinese is often the lingua franca between students from different cultures.

When thinking about these students, indeed there are opportunities in China for them to hear the gospel. Healthy international churches operate in most major cities, many with non-English congregations. Unfortunately Christian students often arrive with the preconception that there is no church in China, therefore they do not seek out fellowships. And though these fellowships certainly welcome any international student who comes, there remain significant barriers to outreach both politically and in terms of capacity.

The national TSPM church, though open, appears to be doing very little in terms of reaching international students. A handful of house churches, both open and more discreet, are recognising the joyful duty of sharing the gospel with international students living in China. While at times feeling ill-equipped, perhaps culturally nervous and under-resourced, they have an excitement about reaching out. Some local campus-based ministries are also beginning to put international students on their radar.

International students in China form a mixed, dynamic, and growing field of ambitious influencers of the next generation from every corner of the world. They are the prime ministers, CEOs, policy-makers and leaders of the future. Cultural complexity meets contextual limitations and ambiguities. Students both thrive and crash with their new-found freedoms in a foreign land.

Is this an invisible and unreached people group?[13] Compared to the West how many organisations or individuals are dedicated to serving international students in China? Are these students the ones to start and strengthen gospel movements back home? What are the challenges and opportunities? What lessons can be shared from decades of ministering to international students in western countries? How does diaspora missiology inform this context? Jyrgal, Lalit, and Tesfay need Jesus.

How, then, can they call on the one they have not believed in? And how can they believe in the one of whom they have not heard? And how can they hear without someone preaching to them? And how can anyone preach unless they are sent? As it is written: “How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news! (Romans 10:14-15)

Who will reach nearly half a million international students with the gospel?

In the next two articles of this series I hope to begin outlining the challenges and opportunities, and attempt to humbly explore these big questions.

Note: The Chinese version of this article can be found at 在华留学生一群未能听到福音的“散居者.”

Image credit: RIDC NeuroMat [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Phil Jones

Phil Jones (pseudonym) and his wife have worked amongst international students including in China for over six years. Their passion is to see international students fall in love with Jesus Christ. Phil also serves as a Lausanne WIN (Worldwide ISM Network) Global Catalyst. To contact Phil, email [email protected].View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.