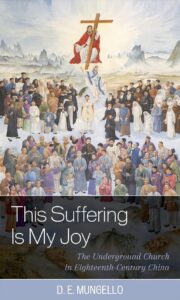

This Suffering is My Joy: The Underground Church in Eighteenth-Century China by D. E. Mungello. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2022, 186 pages. ISBN-10: 1538173972, ISBN-13: 978-1538173978. Available from Amazon.

Following decades of what we now recognize as relative freedom, conditions for Christian flourishing in China today appear to be deteriorating dramatically. Religious policy in China’s “New Era” is reverting back to the ruling elite’s instinctive distrust of all religion (zongjiao 宗教) as heterodox—as demanding allegiance to an alternative authority that is not just politically, religiously, or even ideologically different, but ultimately culturally other.1 Restricting international travel for religious purposes, asserting control over all domestic religious training, threatening believing parents, students, teachers, and administrators throughout the educational system, and preventing all but the very smallest of unregistered religious gatherings: the contemporary Chinese state seems determined to reassert the incompatibility of Christian faith with membership in the great Chinese nation (伟大中华民族).

While overseas cross-cultural workers tend to view today’s tightening in light of the so-called “exodus” of expatriate Christian workers in 1950, this cycle of Christian progress followed by persecution has a much longer pedigree in Chinese history.2 In his latest book This Suffering is My Joy, China historian D. E. Mungello offers a brief study of the Catholic Church in China following the Yongzheng Emperor’s 1724 proscription of Christianity, highlighting how local and expatriate Catholics responded to official persecution over the following century. As priests and missionaries from overseas became more and more rare, Catholic practice and identity in China moved “underground” where it was increasingly sustained and nurtured by local believers.

This Suffering is My Joy develops chronologically, with the focus of each chapter shifting between different aspects of Catholic ministry in China as the nature of that work ebbed and flowed over the century. Throughout the book, great attention is paid to the racial and cultural tensions that too often emerged between expatriate Catholic ministers, their Chinese co-laborers, and the many local believers they both served.

Mungello begins his study by examining Fr. Matteo Ripa’s revolutionary 1729 establishment of the Chinese College in Naples specifically for the purpose of equipping Chinese believers for religious vocations back in China.3 The difficulties involved in establishing the college, the complexities of selecting and transporting the students and especially the many cross-cultural challenges involved are traced through the early years of persecution. In the following chapters, the successes and failures of those students—the first Chinese priests—are presented in detail, while more prominent graduates of Ripa’s college such as the McCartney Embassy translator and eventual Shanxi priest Li Zibiao are discussed in later portions of the book.4

Towards the end of the study, Mungello explores Chinese Catholic responses to state persecution, and in particular the role of Chinese lay people and clergy in the maintenance of Catholic Christian communities during these years of proscription. The study then takes a closer look at the brief emergence of a comparatively Chinese underground church—contrasting it with the more indigenous and isolated Japanese underground church of the seventeenth century—before concluding with a fascinating reflection on martyrdom, comparing the Chinese notion of suffering perseverance motivated by filial loyalty to the saints who have gone before with the European concept of sacrificing one’s life for the gospel.5

Several aspects of this narrative are highly suggestive for the contemporary China ministry community struggling to endure in the New Era. Part two will reflect on some of the lessons today’s China workers can learn from the eighteenth-century Catholic experience.

Read the second part of this review, “Chinese Christianity Endures, Part 2: Learning from the 18th-Century Church Under Authoritarian Rule.”

Our thanks to Rowman & Littlefield Publishers for providing a copy of This Suffering is My Joy: The Underground Church in Eighteenth-Century China by D. E. Mungello for this review.

Endnotes

- Mungello, This Suffering, 152–53. For a general introduction to the concept of “religion” in China today, see the section on “What Religion Means in China” in the Pew Research Center’s August 2023 “Measuring Religion in China,” https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2023/08/30/measuring-religion-in-china/. For more on the imported term zongjiao and the emergence in pre-Republican China of the modern western notion of “religion,” see Vincent Goossaert, “1898: The Beginning of the End for Chinese Religion?” in The Journal of Asian Studies 65, no. 2 (2006): 307-335.

- Phyllis Thompson, China: The Reluctant Exodus (CLC Publications, 2004).

- Mungello, This Suffering, chapter 3.

- For more on the fascinating life and ministry of Li Zibiao, see Henrietta Harrison, The Perils of Interpretating: The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators between Qing China and the British Empire (Princeton University Press, 2021); and especially Harrison, “Naples, China and the Cosmos: The Theology of an Eighteenth-Century Chinese Priest” in The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 2023, 1–19.

- Mungello, This Suffering, chapter 6.

Image credit: via Piqsels.

Swells in the Middle Kingdom

"Swells in the Middle Kingdom" began his life in China as a student back in 1990 and still, to this day, is fascinated by the challenges and blessings of living and working in China.View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.