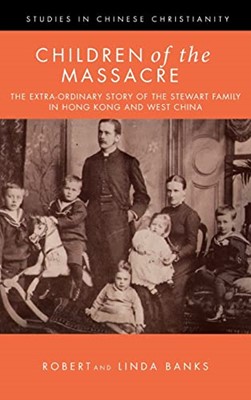

Children of the Massacre: The Extra-ordinary Story of the Stewart Family in Hong Kong and West China (Studies in Chinese Christianity) by Robert & Linda Banks. Pickwick Press, 2021, 192 pages. ISBN-13 9781666725032 (paperback); 9781666720358 (hardcover); 9781666720365 (eBook). All three editions available at Wipf and Stock.

“Resilience” is a current buzz word used in many circles and given heightened attention since the global COVID-19 pandemic has shown its value. But it is not a new attribute. The ability of people to not only survive but thrive and make admirable contributions despite hardships is the stuff of many missionary lives. The six Stewart siblings whose lives are followed in this book certainly exemplify resilience.

In Children of the Massacre: The Extra-ordinary Story of the Stewart Family in Hong Kong and West China, the latest in the Studies of Chinese Christianity series of books, Robert and Linda Banks trace these remarkable children through into adulthood and to their deaths. Despite separation at an early age for education and then being orphaned after an awful attack in Hwasang, Kucheng (now called Huashan, Gutian), Fuzhou in August 1895, their close relationships with one another and ongoing desire to serve the Chinese people is the thread woven into the narrative.

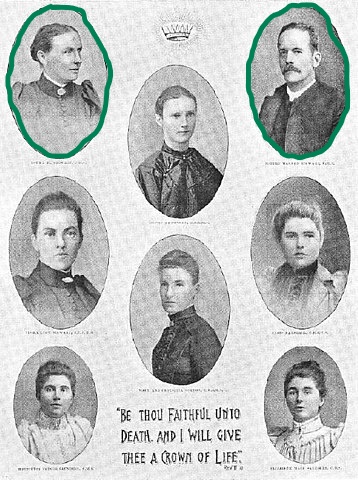

The book’s title puts it as graphically as the news of the day would have presented it: Children of the Massacre. It is more correctly rendered in the Chinese characters— 大屠杀中幸存的孩子们(dà tú shã zhõng xìng cûn de há zi men)— which literally reads “surviving children of the massacre.” The two eldest, Arthur (born in 1877) and Philip (born in 1879), were in Ireland at the time but James (born in 1881), Mildred (born in 1882), Kathleen (born in 1884) and Evan (born in 1892) survived, while Herbert (born in 1889) and baby Hilda (born in 1894) died along with their parents. In that sense, not all of the Stewarts who lived experienced the massacre, but their lives were certainly all impacted.

The use of Chinese interspersed through the book demarcating shifts in the account is not initially obvious and at no point is any explanation given, which may perplex those who don’t read Chinese. Furthermore, for those who do not know the geography of China or don’t know the province of Fujian (Fuchow, also the name of the main city now called Fuzhou), a map would have been useful.

The first chapters explain how Irish-born Robert and Louisa (nee Smyly) came to be in China serving with the Church Missionary Society (CMS), their early married life, and forming their own family. The massacre, candidly described by daughter Kathleen for the press at the time, is recounted. Several single female missionaries were also killed. They had joined the work through Robert’s recruiting drive in Australia, where the family subsequently had some ongoing links. The event no doubt reverberated through the large missionary community throughout China, much as had the 1870 Tianjin Massacre/Incident some twenty years before. The book stays with the family rather than considering the wider responses but does present the anti-foreign context which was to climax in the 1900 Boxer Rebellion/Uprising.

The majority of the book tracks the development and decisions made by the siblings at different points leading them back to Asia. It is indeed “extra-ordinary,” as the subtitle to the book states, that, rather than having an antipathy towards China and Chinese people, all six felt called to return and serve in China in various capacities over the years. They also used the Chinese language first learned in their childhood years in different contexts; for example, to assist Chinese in the Chinese Labour Corps during the First World War.

From the start with the Stewart parents, education was a focus. Robert headed up the CMS Boys’ School in Fuzhou and helped develop a small theological college. Louisa assisted with the CMS Girls’ School. It is noteworthy that Robert actively promoted local Chinese leadership and encouraged the training of Chinese workers. He strongly believed that “China could never be reached except through its own people” (p. 23). The Stewarts also believed that adapting to the local culture was crucial, a belief not always shared by their colleagues.

Their appreciation for Chinese culture and belief in the value of education seem to have been passed on to their children. Both boys and girls received good educations that equipped them for service. Philip became a doctor; James worked as a chaplain and with students; and Arthur, Mildred, Kathleen, and Evan became teachers.

Their wealthy family and the connections they had enabled them to raise funds and make contributions to the construction of several school buildings over the years. Two of the boys contributed to the education of the wealthier Chinese in Hong Kong through St. Stephen’s College (SSC)—Arthur as teacher and, much later, Philip as Medical Officer. At the same time, Kathleen sought to make provision for girls through St. Paul’s College for Girls. At St. Paul’s College for Boys (SPC), they provided educational opportunities for the less wealthy. Arthur was principal there, then Evan followed years later. In these schools, they promoted Chinese leadership. Meanwhile James and Mildred ended up in Sichuan (Szechuan) province—James involved with the fledgling University of Western China and Mildred in a CMS school.

As this all unfolded in the book, I admit to getting lost in myriad acronyms that weren’t always explained. It would also have helped to have a family tree clearly tracing each of the siblings as they married and had their own children.

Throughout, the strong ties maintained by the siblings is evident and remarkable given the challenges of communicating at the time. Philip, Evan, and James were even able to connect on the battlefields of Belgium during the First World War. The two sisters worked alongside their bachelor brothers initially, with Mildred accompanying James and Kathleen supporting Arthur in Hong Kong. The ties were made closer when two brothers married the Lander sisters.

They also worked hard to maintain ties made with Chinese friends and students, as seen by the correspondence between James and his friend C. Y. Yen and Evan working to strengthen the St Paul’s alumni, not least through visiting them in various parts of Asia. Testimony to this is given at the end of the book.

Lessons for Today

What really intrigued me, as someone who has both worked in China and been involved with educational establishments, were some of the abiding principles of such cross-cultural work. Among these were:

- The value and importance of language study

- The need for support back in the “home country,” ideally with family, to provide stability (as did Aunt Tem’s Dublin home for the Stewart children)

- Firm friends in the ”field”

- Sound education as a basis to really contribute (and the family’s wealth clearly enabled good private schooling)

- The importance of building strategic relationships with local leaders and developing a deeper cultural understanding, not least because foreigners are seen as representatives of their various countries

- Keeping in contact with people—in those days this involved much correspondence in the form of letters

- The role of deputation to publicize the work and for recruiting personnel. It was Robert’s willingness to do this not only in the United Kingdom but also in Australia and Canada that led to initial links with both places.

- The need for periods of withdrawal to refresh and realize that one is not indispensable.

- Strong faith and a sense of call with the desire to build for the future—“Forward” was the family motto.

It seems that many of these contribute to resilience and the ability to commit to long-term service.

Similarly, I noticed some of the challenges which still occur even if in slightly different forms:

- Moving on due to retirement or illness and leaving where one has invested so much

- Health issues with limited local medical care, requiring extended periods of recuperation back in Ireland or England, but certainly not idle time

- Political unrest that derails plans (for the Stewarts, both in China and in Ireland, as well as globally with both First and Second World Wars impacting their lives)

- Unrealistic demands by both highly motivated staff and understaffed agencies.

Given all this, the interwoven and mutually supportive lives of these siblings is inspiring, and much can be gleaned at different levels, making it a book well worth reading. A bonus are the extra bits that introduce current family members who were a helpful resource bringing together the pieces, as well as the accounts of various Chinese people who lives were impacted by the work of the Stewarts over the years. Certainly, both would have been part of their aspirations in leaving a legacy that brings glory to God. In their weaknesses, which are not glossed over, he gave strength that underpinned their resilience.

Our thanks to Pickwick Publications, an imprint of Wipf and Stock, for providing a copy of Children of the Massacre: The Extra-ordinary Story of the Stewart Family in Hong Kong and West China for this review.

Image credit: Zichao Zhang via UnSplash

Andrea Klopper

Andrea Klopper has taught in South Africa, the United Kingdom, and China. She has mentored Mandarin language students and developed a cultural orientation and acquisition program which she used in two organizations. She is now being challenged to make friends in a new location and learning a new language. She …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.