Some people have expressed their doubt about China’s recent initiative to “Sinicize” Christianity. They suspect the plan is simply propaganda, empty threats, or show. After all, haven’t we seen similar programs rolled out in the past?

We’ve been there, done that. Or have we?

I suggest there are at least seven ways that this current plan to Sinicize Christianity represents more than mere saber rattling.

1. The “How”

We’ve previously heard declarations for the unregistered church to come into line with the official state church. In practice, this has meant, “Conform or at least shut up.” Enforcement was random and highly dependent on the will of local party cadre. The understood agreement between local authorities and church leaders was this: “Don’t make us lose face and we’ll leave you alone.”

That’s not the current situation. The plan itself is more specific and comprehensive in scope. Since the government announced its intention to Sinicize religion, we’ve seen leaders implement the policies with far more breadth and aggression. In other words, there has been much more “follow through” than in previous years.

Cameras have been installed in churches. Arrests have increased. Curriculum to “re-train” pastors has been written. Even the biggest churches have not been able to avoid conflict. Authorities also have plans to re-translate the Bible to suit their purposes.

As various outlets have reported, the government in Guangzhou is now ready to pay people to snitch on people who are engaged in religious activities deemed illegal (e.g., house churches, theological training, etc.).

The government has even cooperated with other South Asian countries in order to track the activities of Christians who have ties to the Mainland.

2. The “Where”

In the past, official actions against the church have tended to occur in certain places. For example, the southern cities tend to enjoy more liberty than those in the north. That’s no longer the case. Whether in big cities, on the east coast, in the southwest, or Hainan, one can expect authorities to crack down on religious activity.

While the government has always been sensitive about foreigners interacting with minority groups, it has taken more extensive measures in the past year. In Kunming, for instance, leaders have expelled or pressured out a substantial number (perhaps most) of the cross-cultural workers in the area, including entire organizations.

3. The “When”

In previous decades, persecution was seasonal. One could be assured that police would attempt a “spring cleaning” sometime around Easter. Of course, official visits and holidays meant a few churches would serve as sacrificial offerings to the higher-ups in the bureaucratic food chain.

Now, however, Chinese believers as well as foreign workers find no respite with the changing of seasons. Many people have discovered that “waiting it out” does not work. One must decide to take risks while remaining watchful, or else close shop and move away.

4. The “Who”

Another significant difference is that the current initiative does not focus on Christianity; rather, it explicitly addresses all the major religions in China. The severe crackdown in Xinjiang and the expansive growth of re-education camps are just a few indications that the government wants to stifle the growth of all religions, not just the house churches.

5. The “Why” (against)

The rhetoric has changed a bit as well. Specifically, official propaganda is much more “anti-Western” than in previous campaigns. Sinicization is portrayed as a struggle against the oppression and imperialism of Western powers, especially the United States.

In a recent speech, Xu Xiaohong, Chairman of the Chinese Christian Three-Self Patriotic Movement Committee, stated,

In modern times, Christianity was introduced to China on a large scale along with colonial aggression by Western powers. It was called "foreign religion." The churches anywhere in our country were merely the result of Western missions and "Christianity in China." Many believers lack national consciousness, so people say: "One more Christian is one less Chinese." The occurrence of many teaching plans, especially the "Boxer Movement" and the "non-Christian movement", prompted the church to create a "self-reliance movement."

Also,

It must be recognized that the surname of the Chinese church is “Chinese”, not “Western”

These are just a few examples of such comments made by national leaders.

6. The “Why” (for)

What is driving the initiative to Sinicize religion in China?

In one respect, government leaders have always cared more about protecting political power and maintaining social harmony. What many outsiders don’t realize is that China typically has been less concerned with “religion” itself (compared to the sort of persecution one finds in the Middle East).

Over the past year, official propaganda has increasingly and explicitly linked Sinicization with socialism. Sinicization is about ideological purity. Party leaders have learned from the collapse of other communist regimes that allowed compromise to creep in.

Church leaders receiving Sinicization training were recently told that Western cross-cultural workers seeks to encourage “ideological pluralism, which will lead to political pluralism.” Furthermore, the document outlining the 5-year plan explicitly states:

Promote the core values of socialism on campuses and in classrooms with teaching materials that instill them into students' minds. Teaching demonstrations and exchange activities should be organized on the core values of socialism. In theological colleges, develop classroom teaching and campus culture to propagate these values.

7. “How long”

Finally, another development distinguishes recent efforts to Sinicize religion from previous campaigns. Current opposition to the church does not originate with TSPM church leaders, such as the former Bishop Ding (Ting), who wish to curry favor from their political patrons. Instead, Sinicization is the brainchild of China’s highest political authorities. Given the fact that President Xi is no longer restricted by term limits, we have little reason to expect pressure to let up when he leaves office. He will be around long enough to see the process through.

(8.) Co-opting Christian Language

Perhaps we can another difference, though I don’t have a nice heading for it. Government voices have begun to reframe their campaign as a fight for the church itself. One writer explains:

“There will be no official or unofficial church when the church is united," he said. [Bishop Vincent Zhan Silu of Mindong, a member of the consultative conference and vice chairman of the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association]

Asked if it meant the so-called underground church would be forced to disappear, he said: "Don’t you want the church to be united? A church schism is not the fundamental aspiration of Catholics."

Zhan said those Catholics who refused to join the official church were acting in their personal interests, but there was no timetable for the integration of the underground church—those who have refused to register with the government—with Beijing's hierarchy.

The current strategy being employed is comprehensive and coordinated. We can only hope the response from Christian leaders will show corresponding unity and wisdom.

For my previous assessment of China’s Sinicization plan, Read “'Sinicized Christianity' Is Not Christianity."

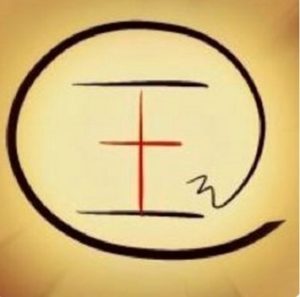

Image courtesy of a ChinaSource reader.

Brad Vaughn

Brad Vaughn (formerly known by the pseudonym Jackson Wu; PhD, Southeastern Baptist) is the theologian in residence with Global Training Network. He previously lived and worked in East Asia for almost two decades, teaching theology and missiology for Chinese pastors. He serves on the Asian/Asian-American theology steering committee of the Evangelical …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.