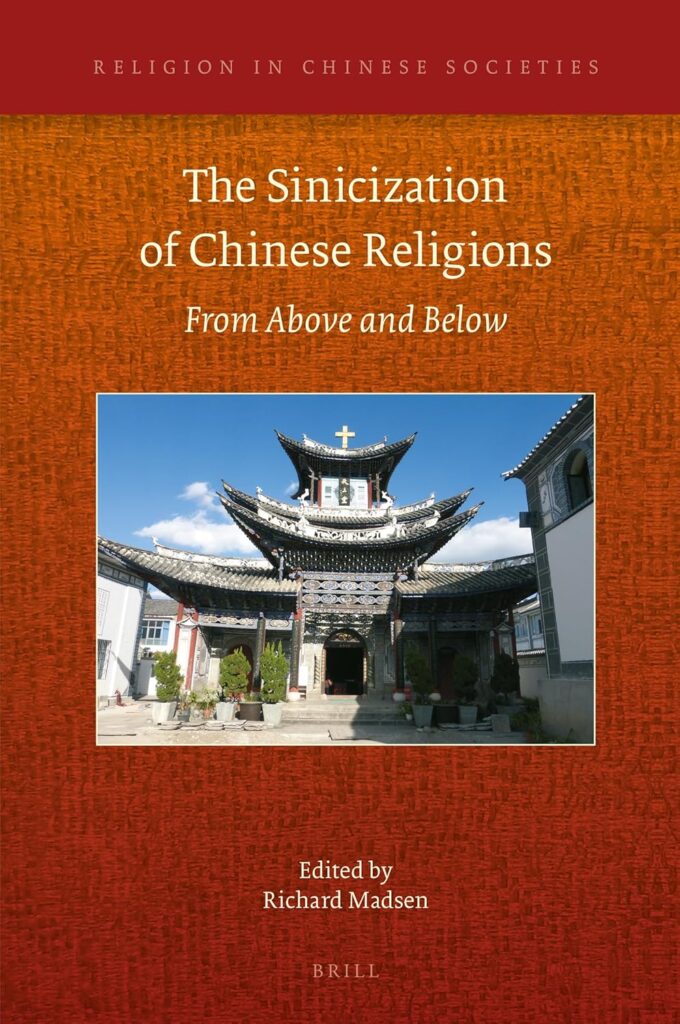

The Sinicization of Chinese Religions: From Above and Below edited by Richard Madsen [Religion in Chinese Societies, Volume:18]. Leiden: Brill, 2021, 192 pages. ISBN-10: 9004465170, ISBN-13: 978-9004465176. Available from Press and Amazon.

…Chinese cultures have proven to be enormously resilient in the face of social and political upheavals over the centuries and have shown great capacity for creative adaptation to changing circumstances. In the long run, perhaps, the Sinicization from below will be more consequential than the Sinicization from above.1

Richard Madsen’s edited volume on the contemporary Sinicization of Chinese religions consists of six dense chapters (in addition to an introduction and a six-page index), which are based on the proceedings of an academic workshop held at the University of California, San Diego, in 2018. The contributions cover the following studies relevant to the Sinicization of religions:

(1) Sinicization as a political discourse and its recent history;

(2) “‘Official Confucianism’ as Newly Sanctioned by the Chinese Communist Party” by Chen Yong;

(3) “The Sinicization of Buddhism and Its Competing Reinventions of Tradition” by Huang Weishan;

(4) “Already Post- Modern. Buddhist Stone Images in Luoyang and the Question of Sinicization” by Wang Dong;

(5) “Faith in the Future/ Practices of the Past. A Sinicized Islamic Revival among the Hui of Xining” by Alexander Stewart;and

(6) “Xiejiao, Cults, and New Religions. Making Sense of the New Un- Sinicized Religions on China’s Fringe” by J. Gordon Melton.

None of these chapters focuses exclusively on Protestant Christianity, although much of the opening chapter does, including a section on Zhongguohua (中國化) in Christian Studies, as does much of Chapter 6, which discusses the stigma and criminalization of some “unorthodox” Christian groups. Filling an important research gap in international scholarship, the volume highlights Sinicization discourses in other Chinese religions, including what Chen Yong calls “official Confucianism” as the Sinicized expression of China’s own ancient tradition. This weighting is significant considering the prominence of the “Sinicization of Protestantism” as compared with the Sinicization of other Chinese faiths, especially in the past twelve years.2

Following the opening chapter on recent policy history, the six chapters of the book are structured thematically from most to least Zhongguohua-ed, i.e., officially “Sinicized,” Chinese religions, that is, from a state-initiated Confucianism—as Chen Yong calls it—to the proscribed “evil” cult. Taken together, the contributors present and problematize a complex interplay between religious groups accruing religious authority to themselves on one hand, and the state controlling religion in the interest of advocating its Sino-socialist narrative on the other. Some key insights can be gleaned here:

- First, what Madsen refers to as “Sinicization from above,” and what Yang calls “Chinafication” in this book have distinct historical trajectories for different ideologies and religions, from Maoist Sinicization to today’s Sinicization-of-religion rhetoric, which varies across religions and locales. This is outlined explicitly in Yang’s chapter.

- Secondly, as the contributions to this issue demonstrate, Zhongguohua is a matter not only of organic adaptations to religious needs that change with the development of religious communities (Madsen’s “Sinicization from below”), but of programmatic rhetorics. Huang Weishan’s chapter on the different narratives by which Buddhism today reinvents and propagates itself in state, academic, and religious discourses, highlights this well in her explications of how China’s Buddhist stories are told.3

- Sinicization is not the only possible direction for a religion in China to develop: some religious communities choose to emphasize internationalization or intentionally maintain foreign ties or elements that are seen as contrasting with elements of Chinese traditional or contemporary identities. Wang Dong’s fascinating chapter illustrates this point.4

- Sinicization is often, though not exclusively, a male-dominated discourse. This is the case for Buddhist clergy reinventing “traditional principles” in the rhetoric of traditionalism.5

- Finally, further studies, especially in terms of ethnographic fieldwork that covers more of today’s Chinese religious traditions, are needed to extend the discussions begun in this volume. Alexander Stewart’s and Huang Weishan’s chapters provide strong examples of research on lived religion, covering some of the diversity of Hui cultural and religious identity expressions in Xining and the complex negotiation of narratives within and about contemporary Chinese Buddhist communities, respectively.

The volume may have benefited from the inclusion of a broader range of Chinese religions, including at least the two other official religions, Catholicism and Taoism, which are not represented. Of course, scholars need not necessarily follow the Chinese government’s designation of official religions, and this compilation also represents its own narrative, pointing to a far more complex reality of religions in Chinese contexts, whose orientations are far from monolithic and led by interests that may clash with the agendas of the state, which has its own rhetoric on the desired direction for Chinese religions.

Madsen’s dichotomy of Sinicization “from above and below” is helpful and restates a general distinction between two discourses. Historian Ying Fuk-tsang, for example, distinguishes between historical movements within Chinese Christianity, for example, and the contemporary rhetoric of Zhongguohua. The former designates missionary indigenization efforts, as well as the Republican-era indigenization movement (本色化運動) initiated by Chinese theologians and church leadership as distinct from and in protest against conservative missionary Christianity; the latter, for Ying, is the government-led policy of Sinicization (中國化). Even a century ago, missionaries had their own terminology to describe the process of the Chinese church becoming Chinese-led. These terms ranged from the “three-self principle” to “naturalization,” the “Nevius Plan,” etc., while the contemporary Sinicization discourse involves the terminology of Chinese style (中國式) and with Chinese characteristics (中國特色) and with reference to the orientation it seeks to promote in the development of Chinese religions: one that is commensurate with Chinese-style modernization and socialist values.6Zhao Zichen spoke of a “national church,” although he understood this in universal terms: each national church had its own historical message to speak to a particular national situation7: this is the important difference between the Chinese Communist Party’s nationalist rhetoric and the narratives of religious groups whose identity connects not only with Chinese culture, but with the international and cross-cultural elements of their faiths as well. This tension rings through the different case studies that make up this edited volume.

Some chapters in the book would have benefited from being updated for publication, especially Chapter 6 on new religious movements and portions of the book based on field research (which at the time would have been difficult to conduct). As the book was published in the midst of a global pandemic that brought new waves of restrictions to Chinese religious congregations across the country, it would be highly beneficial to have this book updated with additional information on the post-COVID state of Chinese religious life. There is depth and theoretical sophistication to the arguments that are presented in this volume, some of which, however, might have been more convincingly related to the contemporary Sinicization (Zhongguohua) of religions (Chapter 2 hardly mentions the term), since this is the terminological set-up a reader coming to the volume will expect. Despite these shortcomings, the work is a must-read for anyone concerned with the direction of Chinese religions and China’s religious policy. It hones in on the difficulty of squaring official rhetoric with lived religious experience when narrating the story of contemporary religious life in China.

Endnotes

- Richard Madsen, “Introduction,” in The Sinicization of Chinese Religions From Above and Below (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 1–15, 14.

- Cf. Yang Fenggang 楊鳳崗, “Sinicization or Chinafication? Cultural Assimilation vs. Political Domestication of Christianity in China and Beyond,” in The Sinicization of Chinese Religions: From Above and Below, ed. Richard Madsen (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 32.

- Cf. Huang Weishan 黃維珊, “The Sinicization of Buddhism and Its Competing Reinventions of Tradition,” in The Sinicization of Chinese Religions from Above and Below,ed. Richard Madsen(Leiden: Brill, 2021), 64-85.

- Cf. Dong Wang, “Already Post-Modern Buddhist Stone Images in Luoyang and the Question of Sinicization,” in The Sinicization of Chinese Religions From Above and Below,ed. Richard Madsen(Leiden: Brill, 2021), 86-129.

- Huang, “The Sinicization of Buddhism,” 75.

- 〈中共中央關於進一步全面深化改革 推進中國式現代化的決定〉 [Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Further Deepening Reform Comprehensively to Advance Chinese Modernization], 中華人民共和國中央人民政府 [the State Council of the People’s Republic of China], July 21, 2024, accessed February 21, 2025, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202407/content_6963770.htm; “Full text of the report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China,” the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, October 25, 2022, accessed February 21, 2025, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/202210/25/content_WS6357df20c6d0a757729e1bfc.html.

- Cf. Zhao Zichen (T. C. Chao) 趙紫宸, “The Relation of the Chinese Church to the Church Universal,” Chinese Recorder, vol. 54, June 1923, 350-353, reprinted in The Collected English Writing of Tsu Chen Chao (Works of T. C. Chao, Vol. 5), ed. Wang Xiaochao (Beijing: China Religious Culture Publisher, 2009), 121-124.

Image credit: Joann Pitmman

Naomi Thurston

Naomi Thurston is a scholar of contemporary Chinese Christianity based at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). Her research focuses on the contributions of Chinese intellectuals to issues in contextual and academic theology and Christian studies. She has translated the writings of contemporary Chinese scholars and currently serves as the director of …View Full Bio