Chinese Christians are not only enduring faithfully—they are creating new spiritual languages for the future.

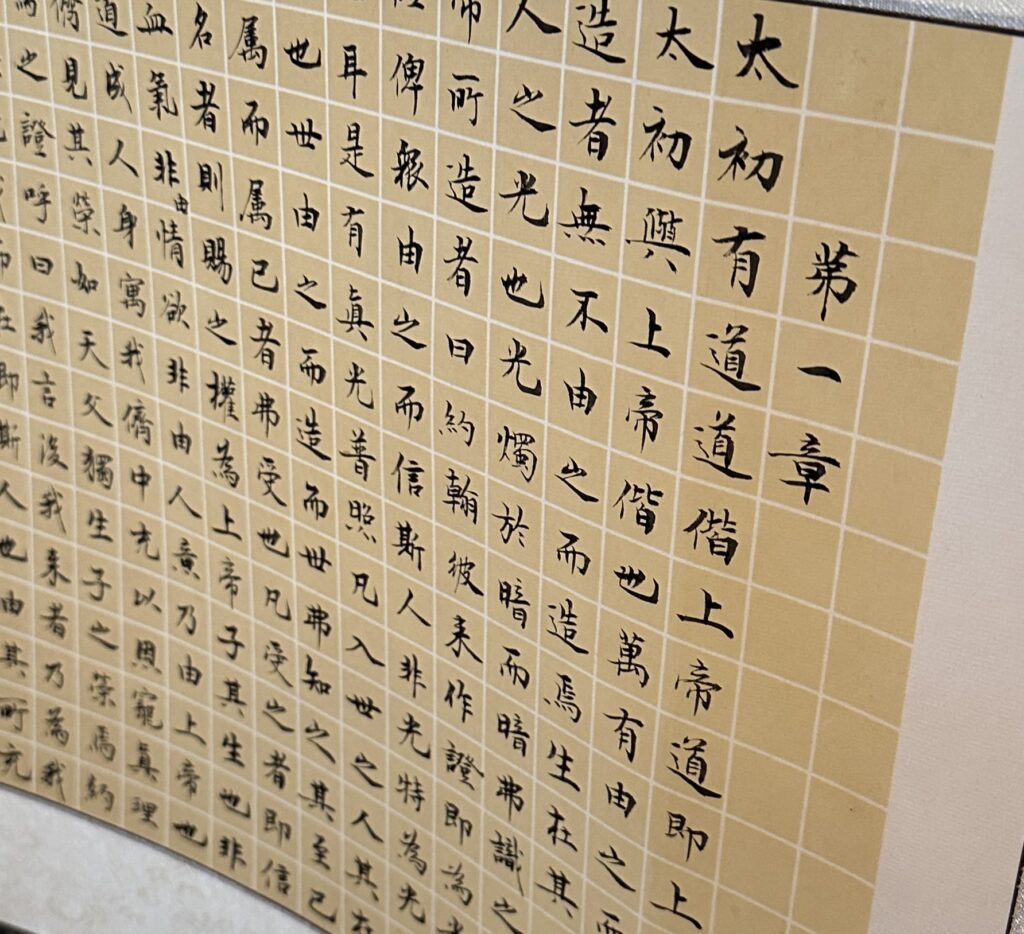

It began with a simple idea—one chapter per person. The initial goal was modest: to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the Chinese Union Version of the Bible, the most beloved and widely used translation among Chinese Christians. Organizers envisioned 1,189 participants, each handcopying a single chapter, to create one complete Bible by hand.

But what followed was far more than anyone anticipated.

Without promotion or platforms, the idea simply spread—through word of mouth, through prayer, through the kind of longing that doesn’t announce itself but runs deep. Churches began printing standardized copy sheets, which were designed by the initiating pastor and somehow uploaded to WeChat communities. Sunday schools joined. Families gathered around dining tables with open Bibles and ballpoint pens. Pastors, teenagers, artists, businesspeople, new believers, elders, and even residents in rehabilitation centers all took part. Some copied a chapter. Others copied entire books. A few copied the entire Bible more than once.

In cities and villages, in crowded apartments and countryside kitchens, the people of God were writing.

And in writing, something happened. This simple act—pen on paper, word by word—became a form of worship. It became a way of remembering, of re-centering, and most unexpectedly, of reconnecting.

A Movement Formed in Silence

There was no fanfare, no headline. But as the movement unfolded, a quiet pattern emerged like a wildfire. What began as an act of personal devotion turned into a bridge between people and places.

One rural congregation copied the Old Testament. An urban fellowship picked up the New. Entire districts of churches joined forces to complete full editions together. Family members—some of whom had never prayed aloud together—found themselves side by side, writing Scripture and rediscovering one another.

In one remarkable instance, a family of lifelong Christians across generations had not been able to sit down together for years because of their denominational differences. They belonged to different church systems—registered and unregistered. But when they each signed up to copy different parts of the Bible, something began to shift. They started exchanging verses, asking about each other’s chapters, and praying together. One of them wrote later, “For the first time, we remembered that we are not just family members by blood—we are all God’s children. The ink reminded us.”

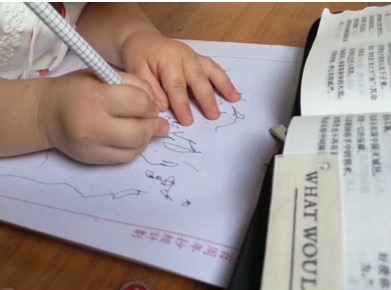

In a time and place where many churches operate in isolation, hand-copying the Bible became a shared language. A woman in her seventies, who had never learned to read, asked her grandchildren to teach her each character stroke by stroke. A man, once paralyzed by addiction, used his left hand—the only one that still functioned—to write his way through Psalms. A toddler sat beside her mother each day, clutching her own sheet of paper and praying before her scribbled “verses.” No one could understand what she wrote—but God could.

Even a group of recovering addicts at a rehabilitation center joined the movement, committing to copy entire books together as part of their healing process. One counselor described it this way: “They didn’t just write the Word—they let the Word rewrite them.” He added with a half-smile, “They might be our most efficient group—perhaps because their days are quiet, and the Word gives them something worth holding onto.”

Where the Word Finds a Home

The movement touched lives far beyond the church walls.

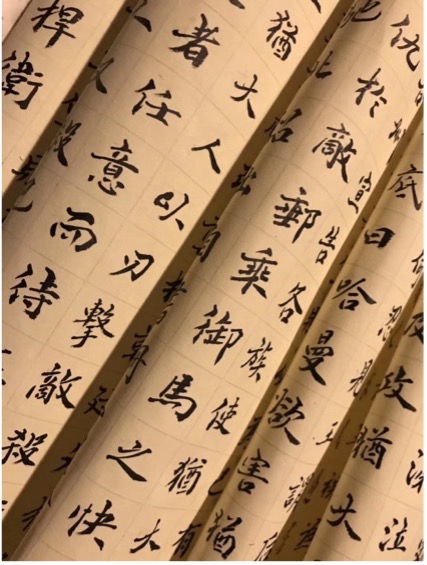

One calligrapher, who had long copied Buddhist and Taoist texts and was even known for it in artistic circles, encountered the Bible for the first time through this project. Curious, he signed up to hand-copy the Gospel of John. When his handcopied manuscript arrived weeks later, those overseeing the project were stunned—not just by the elegant brushwork, but by the depth of care in every stroke.

And something had shifted.

He kept copying. And as he copied, he began asking questions. Soon, the words were not only being written into his notebooks—they were being written onto his heart. That year, he was baptized, surrounded by friends from the art and charity communities. The gospel he once approached as an outsider had become his own.

Another participant—a Sunday school teacher—had grown weary. Her ministry was burdened by distraction, and even her fellow teachers were often absorbed in digital games and constant activity. So she made a decision: to copy the entire Bible by hand, as a way to seek stillness again. Over time, her body began to heal, her heart grew quiet, and her love for Scripture deepened. By the time she finished her second full copy, she had gone through 170 pens.

When the Word Becomes Flesh Again

What emerged from this movement was not only unity across churches, but a renewal of reverence. The Scriptures became more than a text to study or recite—they became something to dwell in, to hold close, to trace with one’s own hand and tears.

In a digital age saturated with content and commentary, this return to slowness was not accidental—it was prophetic. Copying Scripture requires time. It demands stillness. It invites meditation. And it resists distraction.

Participants shared how the practice softened their hearts, calmed their spirits, and rekindled a love for God’s Word they hadn’t known they’d lost. One woman wrote that after months of writing by hand, she no longer felt the need to rush through morning devotions. “The verses are staying with me now,” she said. “They are not just in my Bible—they are in me.”

And then there was the woman who could not read, yet finished copying the entire New Testament. Or the elderly man in a wheelchair who traced every letter with trembling fingers. Or the teenager with autism who illustrated entire chapters with scenes of quiet joy and unshakable faith.

This was not a mass campaign. It was not polished or promoted. And perhaps that is why it grew. Because it asked for nothing but faithfulness. Because it offered nothing but the Word.

The Gentle Invitation

This was not aesthetic spirituality—it was costly faithfulness. Handcopying the Word was never just romantic. It was reverent. And through it, something real took root.

Some scholars have observed that this movement created what they call an “alter-public”—a sacred, digital-physical space shaped not through resistance, but through reverence.1 In choosing to write rather than to speak, Chinese Christians have quietly reclaimed spiritual agency in a society where silence is often safer than visibility. This insight sharpens the contrast: while many of us enjoy religious freedom, we sometimes squander it in distraction. They, constrained, rediscovered the power of the Word through devotion.

For those of us in churches where Bibles are freely printed, stacked on bookshelves, and quietly ignored, this movement is not just inspiring—it is exposing. It shows us what it means to treat the Word not as a resource, but as a treasure.

We often admire the perseverance of believers in restricted environments. But what if the deeper lesson is not in their suffering—but in their seriousness? While some copy in secret and in silence, we browse in abundance and forget. While they write to remember, we forget because we no longer write.

The handcopied Bible movement continues. Pages are still being filled. Stories are still being told.

Its legacy may not be in numbers but in the slow, hidden ways it has shaped lives. In the way it has drawn families closer. In how it has bridged denominational divides. In how it has reminded the church—scattered, weary, and often hurried—what it means to return to the Word not just in study, but in stillness.

Sometimes, unity doesn’t begin with big statements. Sometimes it begins with a pen. Sometimes, revival doesn’t sound like a sermon. It sounds like silence—interrupted only by the turning of a page.

We who live amid speed and surplus may find in this quiet movement from the Chinese church offers a question worth carrying:

What have we forgotten in our freedom? We are not limited by ink, paper, or fear. Yet somehow, we drift.

Perhaps what we lack is not access—but awe.

Perhaps what we need is not more teaching—but more trembling.

What might we remember—if we simply slowed down and began to write again?

He is to write for himself on a scroll a copy of this law… It is to be with him, and he is to read it all the days of his life (Deuteronomy 17:18–19, NIV).

May the words we write become the truth we live.

May the ink on the page lead us deeper into the presence of the One who first spoke it.

Endnotes

- For further insight into the deeper social and theological implications of this movement, see Carsten Vala and Jianbo Huang, “Online and Offline Religion in China: A Protestant WeChat ‘Alter-Public’ through the Bible Handcopying Movement,” Religions 10, no. 10 (2019): 561. Their research explores how this act of Scripture copying became both a spiritual discipline and a subtle reclaiming of shared religious space.

Image credit: A friend of ChinaSource

Andrea Lee

Andrea Lee writes at the intersection of faith, culture, and Chinese Christianity.As Content Manager at ChinaSource, she curates stories, nurtures a community of writers, and shapes the editorial direction to reflect the depth and diversity of the Chinese church experience. Born and raised in Taiwan, Andrea studied Chinese Literature at Tunghai …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.