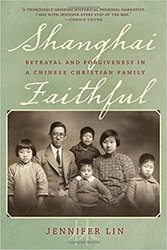

In a post last summer, I wrote about Jennifer Lin’s book, Shanghai Faithful: Betrayal and Forgiveness in a Chinese Christian Family:

In a post last summer, I wrote about Jennifer Lin’s book, Shanghai Faithful: Betrayal and Forgiveness in a Chinese Christian Family:

When a Catholic Chinese-American journalist discovers that her grandfather was a prominent Anglican church leader in China in the 1940s and that her granduncle was none other than the famous house church leader, Watchman Nee, she did what every good journalist does—she set out to tell the story.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with the author about her book. I put to her three questions:

3 Questions

1. How did you come to learn about the unique roles of your grandfather and grand-uncle in the Chinese church?

My father was part of the diaspora that came to the United States in 1949. Based on the letters that my grandfather sent to my parents, beginning in 1953, my understanding of him was simple, namely that he was a retired priest who took care of his grandchildren. My father also told us that his father’s brother-in-law, Watchman Nee, was a famous religious leader in China who had many followers. Because we were part of the Catholic community, we didn’t know too much about him. It wasn’t until later, when I read Nee’s book Against the Tide, that I understood what a controversial figure he had become in China, and of his arrest and being labeled a counter-revolutionary.

What I didn’t understand until I went to China for the first time in 1979 was how the politics of the time were playing out in my family, and how their relationship to Watchman Nee had caused severe problems for them. As I started researching and digging deeper into archives and records, and reading everything I could about that time period, I realized how my grandfather’s life was upended in 1949 and that his actual work within the church became very limited. I came to understand just how tumultuous their lives had been. This was true, not just after 1949, but as early as the 1920s. I discovered things that my father was clueless about, such as my grandfather being forced to stand before his parishioners in Shanghai to denounce his mentor.

After learning all of this, I began to see his letters and photographs in a different way. There is a photo from 1956, taken on his birthday. He is standing in his full Anglican garb, holding a Bible. He is almost smiling. Part of my work as a reporter is connecting the dots. When I looked at the date on the photo, I realized that it was taken the very year his brother-in-law had been publicly denounced and sentenced to prison. His wife was caught up in the turmoil, but there he stands, looking almost defiant.

2. What was one of the most important discoveries that you made?

The most important discovery for me was learning what happened to my grandfather in Fuzhou in 1927. There were many anti-foreign and anti-Christian incidents, and in one of them, my grandfather was paraded through the streets wearing a dunce cap. I found out about that incident by reading the index of Ryan Dunch’s book Fuzhou Protestants and the Making of Modern China, 1857-1927. The first thing I did when I picked up the book was check the index (it’s a quirky habit of mine) for my grandfather’s name.

There was one sentence in the book about how my grandfather had been captured by a mob and paraded through the streets. I contacted the author who directed me to a primary source description of the event. We often associate this type of anti-Christian violence with the Cultural Revolution, but this was 1927.

This led me to the Church Missionary Society (CMS) archives in Birmingham, UK where I found a reference to the event by the bishop in a letter written to the home office. I found another letter from an American missionary who was with the Fukien Christian University which included actual quotes of what my grandfather was saying.

Newspaper reports and diplomatic archives filled in many of the details, including the fact that some in the mob were carrying pistols.

I also found the memoir of my grandfather’s mentor that referenced the incident. He and my grandfather had been corresponding and in a letter he described what he was thinking at the moment he was captured by the mob.

I shared all of this with my aunt and father and none of them had ever heard the story. It was an important moment in my grandfather’s life, but he had never talked about it with his children. So, in terms of my research, that was the most important thing I found. It showed me, not only the depth of his faith, but of his courage.

3. Can you speak a bit about the subtitle of the book, “Betrayal and Forgiveness in a Chinese Family.”

Researching the book revealed to me how much stress existed within the family. During the Cultural Revolution, my cousins were bombarded daily with accusations against their parents and grandparents. As a result, they tried to distance themselves from the family’s religious path, and at one point even declaring to their grandmother that they were “on the other side.” In time, however, the older generation forgave them for their betrayal during that time.

The other thing I realized was that my grandfather was both a victim of betrayal and a perpetrator. He was attacked for being a “running dog” in 1927, but in 1952 he had to stand before his fellow parishioners and accuse his mentor of being a “running dog.” He had to betray someone close to him. In examining the Mao years, it was never enough to say you were loyal, you had to prove it. And proving it meant denouncing those who were close to you. That was the way they survived.

Images courtesy of Jennifer Lin.

Joann Pittman

Joann Pittman is Vice President of Partnership and China Engagement and editor of ZGBriefs. Prior to joining ChinaSource, Joann spent 28 years working in China, as an English teacher, language student, program director, and cross-cultural trainer for organizations and businesses engaged in China. She has also taught Chinese at the University …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.