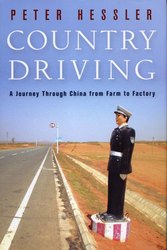

Country Driving: A Journey through China from Farm to Factory by Peter Hessler. Harper (New York: 2010), 438pp. ISBN 978-0-06-180409-0, $27.99.

Reviewed by Wayne Martindale

You sense adventure when you learn that Hessler gets a Chinese driver’s license in 2001, rents a Chinese-made Jeep Cherokee in Beijing, and loads it with such traveling essentials as Oreos, Dove bars, Gatorade and Coke to explore along the farthest reaches of the Great Wall until it disappears in the barren Gobi desert in western Gansu province. In two long journeys and several short ones, Hessler logs 7,000 miles of solo travelsnot recommended, even if you have lived in China for several years and are fluent in the language like Hessler.

But the Wall trip is only the first of three long explorations. Altogether, Country Driving covers a large swath of China over a seven-year stretch and is organized into three roughly chronological “books” or parts called: “The Wall,” “The Village,” “The Factory.” Each part begins with a map of the area chronicled. If time or interest is limited, any of the three sections can be read alone easily enough.

The basic premises of Peter Hessler’s Country Driving will not be new to regular readers of ChinaSource: China is in the midst of the largest urban migration and most rapid industrialization in history. But like his other two books, River Town (2001) and Oracle Bones (2006), this one is vastly informative and delivers vintage Hessler: a happy blend of in-depth personal observation, journalistic investigation, historical researchand wit.

In each section, the number of subthemes and customs woven artfully into the main narrative are enormous. We learn a great deal about driving and village life in Book I; education, hospitals, and small-town politics in Book II; and business and economic development in Book III. Hesssler includes a few notes on sources, but no index, alas, which would include everything from funerals to feng shui, and health care to child care.

Book I, “The Wall,” recounts a journey on newly opened roads, guided by sight of the Great Wall and using a semi-reliable Chinese atlas published by Sinomaps. Along the small towns more or less near the Wall, we glimpse the depopulating villages, where the older generation cares for the children, but where young people (mostly young women in city clothes and high heels) are only to be seen hitchhiking for a visit home. In many of these villages, the kids may be the last generation to grow up there.

This section has lots of history and description of The Great Wall as it morphs from brick or stone to tamped earth, depending on locally available building materials, and from national barrier to national symbol. In contrast to the popular view, Hessler agrees with David Spindler that the Ming Walls really worked as part of an overall defensive strategy.

Naturally, a book like this is filled with travel lore and sprinkled with statistics. The country’s new mobility and explosive development has been fueled by massive government investment in nationwide road building on the American model. Beijing alone has over a thousand new drivers a day, despite the expensive and time-consuming requirements of a medical exam, written exam, technical course, and two-day driving test often irrelevant to real driving.

We all have funny (and terrifying) stories about learning to drive, but imagine a whole country learning to drive at the same time. The book is worth it for the entertainment value. For example, everyone who has visited China knows that its drivers love their horns. But what does all that honking mean? Hessler interprets the length and duration of the blasts as though it were a tonal language, something on the order of Cantonese in its complexity. On the grim side, in 2001, China had one-fifth the number of cars as the U. S., but twice the number of fatalities. By the first quarter 2009, Chinese out-paced Americans in purchasing more vehicles, and by 2020, China will have more roads than the U.S.

Hessler’s drive along the Great Wall through Inner Mongolia occasions reflections on the complex relationship between the Han Chinese and the Mongols. He stops to visit the mausoleum of Genghis Khanthere’s no body; a fake mausoleum with fake history, making the Khan out to be a Chinese hero. In reality, the Mongol conquest that launched the Yuan dynasty in 1279 spurred the massive wall-building of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) to repulse the raiding by the descendents of the Khan’s countrymen. These are the walls of popular imagination.

Book II, “The Village,” follows six years of growth in a sleepy village named Sancha, where Hessler has found a “writer’s retreat.” It is north of Beijing and just beyond the first wall in the honeycomb construction of The Great Wall. Within the village, Hessler follows the Wei family as they struggle through the traumas of poverty to the traumas of prosperity, which sees the father in the family building an inn and restaurant catering to the newly rich of Beijing, who come north with the paved roads and their new automobiles to escape the success of the city. With growing prosperity, there is increased stress and decreased happiness.

Since he had a car, early in the Sancha stay, Hessler was called on to rush the Weis’ son to a Beijing hospital where he would need a blood transfusion for low white cell count. This occasions observations on discrimination against the poor, commonly contaminated blood supplies, and generally unhealthy medical practices. Fortunately, Hessler tapped into the knowledge of some medical friends in the U. S. and Wei Jia pulled through.

The growing prosperity of the Wei family provides a window into how business is conducted in China and its tie with politics, the shady process of buying a used car, family tensions, the decline in health from junk food and constant TV, the disenfranchised wife and mother’s reliance on a fortuneteller to manage her life. On modern China generally, Hessler ventures these salient observations: “Many people were searching; they longed for some kind of religious or philosophical truth, and they wanted a meaningful connection with others” (263), and “rarely did I know a Chinese couple who seemed happy together” (264). So much opportunity, so much prosperity, so little peace.

Small-town culture from health and education to business and politics–along with the smoking, drinking, and banqueting requirements to curry business and political favor–are the chief concerns of this section. The family’s older mentally impaired child gives occasion for observation on policy and attitudes regarding disability.

In the first “book,” Hessler describes the villages that are emptying out. In the third and final book, he describes new cities filling up with industry. This time Hessler rents a car in the established business city of Wenzhou and follows a two-lane road, slated to become an expressway, to the small mountain village of Lishui in southern Zhejiang province. From 2005 to the present, Hessler observes the conversion of Lishui from poor mountainous village to factory town. The advent of a four-lane expressway cuts travel time from the established business center of Wenzhou in southern Zhejiang from an unreliable two hours plus to just over an hour. At the other end of the expressway, the government creates a special economic zone by leveling 108 mountains.

As a point of focus, Hessler relates the fortunes of an uncle-nephew partnership from Wenzhou who start a factory with a niche market making metal bra rings. He also relates the ups and downs of the technicians and laborers who come and go. Hessler even follows the history of the European-made machine that bonds the coating to the metal rings to a knock-off made from memory by a Chinese repairman in southern China. Eventually, there are multiple copy-cat factories as success is observed in the Lishui bra ring factory, which moves to a newly declared green zone to gain a temporary economic edge because the short-term leases are cheap and nobody pays attention to businesses slated for removal. When the account breaks off, the whole economic zone in Lishui is mid-expansion to four times its original size, the land claimed by leveling another four hundred mountains.

Such economic zones are magnets for both entrepreneurs and laborers, full of double dealing, broken promises, and trial and error. This look at the harsh world of Chinese business and factory life can be supplemented by Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China (2008), a recent successful book written by Hessler’s wife, Leslie T. Chang.

Hessler’s book does a good job of giving faces and personalities to the Chinese who are all affected by this new physical and economic mobility. He tells us where they are from, where they are going, what their aspirations and hardships are along the way, and how and why the government leads and responds. His treatment of Christianity is spare, especially for a place like Wenzhou, to which David Aikman devotes a chapter in his Jesus in Beijing, estimating the Christian population at ten to fourteen percent a decade ago. But Hessler is keen enough to observe that, “The new pursuit of wealth can seem empty and exhausting . Some turn to religion .” As Hessler says with requisite humility, “Nobody has today’s China figured out,” but his book, though not written from a Christian perspective, can only help in getting the current lay of the land, and highlights the need for the permanent and truly satisfying.

Image credit: Dusty Roads by David Woo, on Flickr

Wayne Martindale

Dr. Wayne Martindale, professor of English at Wheaton College, has taught in China with his wife, Nita, five times since 1989. He is co-editor of The Quotable Lewis and author of Beyond the Shadowlands: C. S. Lewis on Heaven and Hell.View Full Bio